|

| courtesy: www.wallpaperspictures.net |

I wrote this letter by way of thanking Martin Scorsese for having restored Nidhanaya last year. The letter was written in April this year. Words cannot do justice to him. There have been attempts made here to salvage our cinema. They have always been too little, too late. Scorsese is different. We as Sri Lankans ought to be grateful for that. And for him.

Dear Mr. Scorsese,

How does one begin a letter

of appreciation? I do not pretend to be an avid letter-writer. On the contrary,

I rarely write them, and when I do, I am almost never sure as to the adequacy

of their feeling. What I want to appreciate here, dear Sir, is, first as a Sri

Lankan, second as a passionate lover of the cinema, your successful restoration

of what is considered to be this country’s greatest film – Nidhanaya.

For seven years we thought it lost. Then, inadvertently, we found it in India,

and we feared it would get lost again.

But then, you, with the

World Cinema Foundation, sought to restore it to the glory and pristine

freshness with which it had always meant to be seen. I admit none of us has

actually seen this 4k copy of the film – not even its director, who owing to

his health was unable to head the delegation that went to Venice to see it –

but of its brilliance I am quite sure! It may interest you to know that this

was the second such restoration of a Sri Lankan film, the first being Gamperaliya,

also by Nidhanaya’s director, seven years ago, by the UCLA.

It is to people such as

yourself, and not to bureaucratic policymakers slugging out their duties till

the very end, that we (my countrymen and I) owe this token of gratitude. I

remember with what desolation Lester James Peries, the founder of our cinema

(and Nidhanaya’s director) broke the news of his greatest film’s loss

(the equatorial climate is not friendly to celluloid, as our National Film

Corporation learnt that day); I also remember the lack of anger or malice,

which a lesser artist would have exhibited in such a situation, evident in his

face when he did so.

That Nidhanaya was

discovered (it still remains a mystery how it got to Pune!), and that its

restoration fittingly coincided with Dr. Peries’ 94th birthday,

leaves one little to ask for. Indeed, Dr. Peries is still as lively, as

energetic, in his mental faculties, as he always has been. He celebrated his 95th

birthday a few weeks back, an event which again coincided with another

milestone in our cinema: the opening of Sri Lanka’s very first National

Archives, to record and preserve various films, archival documents and

such-like for the benefit of generations to come.

Admittedly this seems a

little too late, especially in an era where restoration has become more

important than preservation. But in a country as ours, where politicking has

unfortunately all but completely left cultural activity stale and neglected

(there is no real Ministry here to overlook the cinema, for instance), the clichéd

adage “Better Late Than Never” sticks in my mind. I am not adulating the

present administration, but it remains to be said that in the 66 years of

independence since 1948, it is the only government that has given film

preservation any serious attention. I, for one, hope that restoration of our

greatest films – so many of them to list, in fact – will not be a thing too far

off into the future.

My acquaintance with Dr.

Peries – which came about more by accident than will – has been instrumental in

my appreciation of my own country’s cinema, which, as you will realize later

on, is not at all that satisfactory presently. Andrew Robinson wrote The

Inner Eye on Satyajit Ray, while Donald Richie wrote The Films of Akira

Kurosawa on that inimitable giant of the cinema. But no serious book has

been, as of yet, written on Lester James Peries – a pity, given that he is

still among us. I do not rightly remember who it was that said it, but Dr.

Peries ranks with Kurosawa and Ray among the pantheon of filmmakers that

introduced Asian cinema to the world. All three hailed from the same tradition,

from which other directors – Ghatak and Sen in Bengal, Ozu and Mizoguchi in

Japan – emerged.

It is most unfortunate that

we in Sri Lanka had to count on India as our foremost cultural influence –

unfortunate not because of Indian culture itself, but because many of our own

artists, moved by the slick exterior of that culture, expressed themselves

through superficial gloss that was genuine only as products of chic advertising

photography. Nowhere was this truer than in cinema. Dr. Peries has rightly said

that our film industry had a false start. Kadawunu Poronduwa (The

Broken Promise, 1947) was our first sound film. It was shot completely in a

studio in Madras, and was filled with melodramatic cadences only Mrs. Amanda Mckittrick-Ros

could have equalled in bathos.

The entire first decade of

our cinema continued this sorry trend, reusing old formulas and adapting Indian

stories that would never have fitted the canvas of Lankan life. Even the titles

of these films – Kapati Arakshakaya (The Cunning Guardian), Perelena

Iranama (Dashed Dreams), Sangavunu Pirithura (The

Concealed Letter) – reveal their essential, glossy artifice.

But from here onwards, we

differed a little from India. Long before Satyajit Ray, India produced Bimal

Roy, who despite having commercial tendencies in his films (Do Bigha Zameen,

Madhumati) was, I have read, influenced heavily by neo-realism. Sri

Lanka never produced a Bimal Roy. We continued, on the contrary, with the

“slick”, manufactured brand of realism only opium factories could have equalled

in strength.

In a way, a similarity can

be drawn between Peries and Ray. Bengali cinema too, like our own, was

stultified and desultory by the time Ray started to make Pather Panchali.

Like our cinema, Bengali films at the time consisted partly of “to the letter”

adaptations of popular novels. Eager to exploit the racial sentiments of our people,

commercial film producers churned out adaptation after adaptation of

propagandist, Ros-like passionate outcries of anti-Western, mild chauvinism. I

am happy to tell you that most of these films, or at least certain sequences

from them, can be watched for free on YouTube. They are actually quite

insightful for any student who wishes to examine our cinema.

The odds against Ray,

therefore, were roughly the same as those against Peries. Rekawa, his

first film, came barely a year after Pather Panchali had been made. No

two films, coming from the same subcontinent, could have resembled each other

more. Pather Panchali went to Cannes. So did Rekawa. Of course

Ray’s debut was a hit at the box-office, while Rekawa failed (our

audience at the time expected nothing short of opium dreams at the cinemas –

this was clearly not something they were after). Derek Elli later called it as

being “every bit as important a first film as Pather Panchali”. It is

astonishing to realize that neither director knew of what the other was doing

at the time – perhaps the only example in film history of such a thing

happening.

But here too, I think, a

difference can be drawn. Ray’s efforts were vindicated after a matter of three

or four films, and audiences grew to love his approach to the cinema, as did

local critics. I am not so sure with regard to Peries. Ray’s films derived

support from the box-office – that is not to say they were big hits, but rather

that they managed to recoup their costs respectably from Bengal (“Whatever

comes from abroad is extra,” Ray once said) – whereas our critical fraternity

and audiences (I am not disparaging them) were unforgivably slow in their

appreciation of Peries.

This explains why, between

1957 and 1967, he made only five films, whereas Ray had made 14. Not because

Peries was more concerned with the quality than quantity of his output –

however valid that may be in his context – but because, being a maker of

serious, un-commercial films in Sri Lanka, he was being ignored by an audience

that still clung onto glossy remakes of South Indian films.

One of our ablest critics,

Philip Cooray, called him the “lonely artist”. If he was, which we are sure of,

it was because his preoccupation was to communicate with his countrymen, his

compatriots, through a more refined form of art – not the sort of refinement

one sees in a film by, say, Bresson or Kubrick (two directors who shared the

same film-to-year ratio of Peries), but a refinement that asked its audiences

to appreciate a more indigenous, genuinely felt cinema. A cinema of the heart

was what he had been aiming at all this time, and yet, owing to politics and

audience prejudices, I do not think – and I am slightly troubled by this – that

he ever achieved his potential. He came nearest to it in Nidhanaya, but

since then his films never reached the standard set by that remarkable

masterpiece.

Many, including me, are

convinced that the only Asian filmmaker who remained close to Satyajit Ray’s

craft was Peries. This is not because other filmmakers had nothing in common

with him. But in terms of pace, style, attitude and a willingness to assimilate

Western humanism, as Ray himself once remarked, Lester James Peries was his “closest

relative East of the Suez”. Ghatak and Sen were his compatriots in Bengal,

true, but both differ from him in their near obsessive, conscious examination

of social issues, which often – as in Ghatak’s Ajantrik or Sen’s Bhuvan

Shome – takes precedence to a robust, humanist approach to their

characters.

Kurosawa, one is tempted to

call Ray’s closest ally – particularly owing to his willingness to take in

Western tradition – but his dictum “movies must move”, his penchant for

violence and his continual use of universal themes make him share little with

Ray, whose films are noted for their slow pace, their absence of violence, and

their use of regional and simple themes, at second glance.

And as for Ozu and

Mizoguchi, their almost anachronistic refusal to imbibe Western film technique

– as witness a film like Ugetsu Monogatari and its flowing, scroll-like

use of the camera – makes them, again, differ from Ray’s liberal synthesis of

Orient and Occident (indeed, after Tagore, many consider Ray as the greatest

artist Bengal ever produced for that very same reason). This leaves us with Peries,

who in all respects was more likely than not Ray’s closest friend in the East.

It shall always be so, I very much suspect.

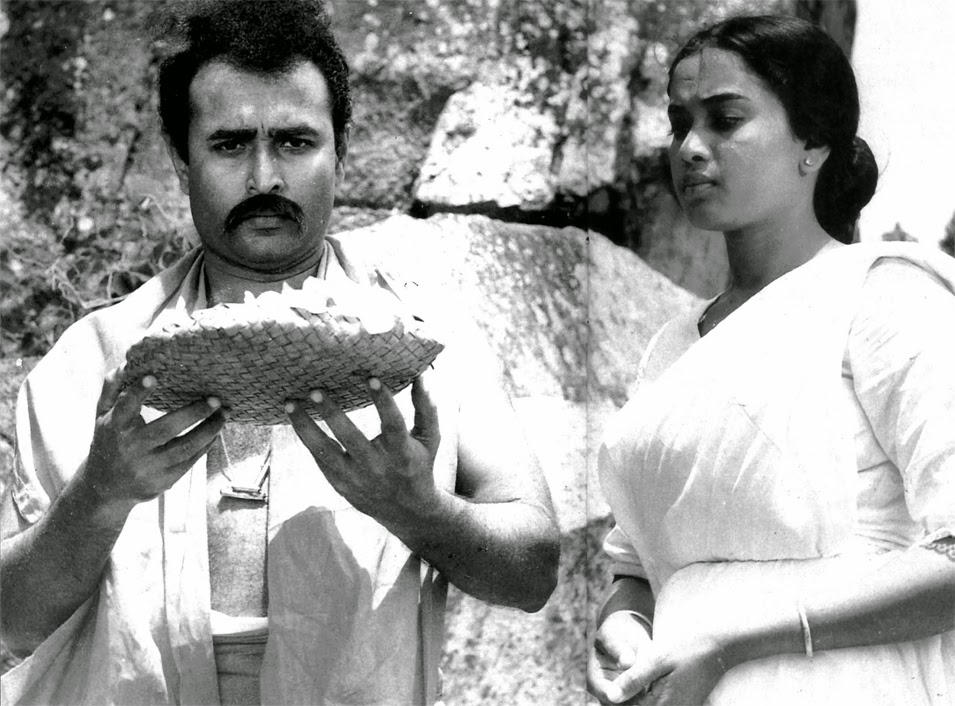

|

| Nidhanaya |

This is the closest Peries

ever got to being described as a cynic. Out of all his films, Nidhanaya

is the only one in which its main character realizes that he had a capacity for

change right throughout, but failed to make use of it, instead driving him onto

an irrationality that would only mean death. Shakespeare immediately jumps into

my mind when thinking of him – Willie Abeynayaka is more Othello than Macbeth,

purely because, like Willie and the Ola Leaf manuscript that is the root of his

murderous obsession, Othello was moved into killing Desdemona by a jealousy

rooted in nothing more than hearsay and irrationality. Peries’ films had

hitherto ended on hopeful notes, with their characters always finding

reconciliation.

Perhaps this was owing to

the prescient vision with which he made Nidhanaya. In his own words, it

is his most controversial. It was an indictment on the political regime of the

day, and came at a time when revolution was seething underneath. Maoist and Marxist

radicals were beginning to incite unemployed youth to violence as a response to

an increasingly overbearing State.

Unlike other socially and

politically “aware” filmmakers, however, Peries does not reserve criticism for

the government alone in his film: the character of Willie Abeynayaka, who

dabbles in superstition to escape his financial troubles, can just as validly

symbolize the graduates themselves, who dabbled in extreme ideology before

violence would overpower them.

It is ironic, moreover, that

within a year of Nidhanaya’s release, one of the bloodiest insurrections

in the history of our country happened. It left more than a thousand dead, many

lying in the streets by the dozen. In this way, I feel, Peries was more

prescient about the things to come, as one would say, than even some of our

most avowedly political filmmakers and artists around that time.

It is also ironic that some

of those same so-called political artists leisurely bite away at Peries when

given the opportunity to do so – “elitist” and “indifferent” being the two

commonest adjectives they use to describe his films. Coming from artists (I

myself have interviewed some of them, and have, so to speak, caught them in the

act) who seem more concerned with portraying their attitude through abstruse

symbols and political slogans than actual human beings, this is not surprising

– but this does not pare down my disappointment. Another unfortunate tendency

amongst some of our artists, predominantly singers, but also filmmakers, is to

disparage one another’s career with personal malice.

The exception, towering

above them all, is Peries. I do not know whether you have personally talked

with him, dear Sir, but doing so for 30 minutes straight will make you realize

what a modest – an intensely modest – man he is. Neither submissive nor

overbearing, he almost sounds, and looks, as though from an altogether

different era. Like the true Oriental artist (here I quote Ray again), he is

all “calm without, fire within”. His ability to make fun at himself, take offence at nothing, makes him perhaps the least self-cantered artist in

a country where, unfortunately, filmmakers, vocalists, composers, playwrights

and the like all jab one another to boost their egos.

Unfortunately, however, his being the exception has not spared him from jabs by other artists. No doubt

influenced by the Czechs and the Nouvelle Vague, these politically

inclined directors I spoke of earlier disparaged Peries as a “Big Papa”, a

purveyor of what the French called “Cinema de Papa”. In fact an almost literal

translation of that phrase was used to describe him – “Appochchi Ge Cinemawa”

(Cinema of the Papa) was a pamphlet, I’ve been told, that was issued at the

premiere of a film by one of these directors. Fashionable and easy, but plainly

imitative and artless.

This ruthless, uncalled for

disparagement did not even escape a collection of his own essays, the foreword

to which was written by a noted political activist who, for no good or

constructive reason, wrote point-blank that she “did not like some of his

films”. Perhaps in a journal or a book of criticism that would have done, but

in a foreword to a collection of his essays? Highly uncalled for, but perhaps

such “activists” derive a fetishistic pleasure from disparaging his films.

Peries himself once told me,

wittily and not without humour, that he was considered a “roadblock” by them

during the 1970s. This may well explain the turn of the critical tide that

greeted his post-Nidhanaya period, an era where political turmoil meant

that films about middle-class life, families and individuals (which were what

he made, and continued to make) were fashionably unfashionable.

Personal malice and

politicking, of course, have always been impediments to any creative artistic

resurgence, and we in Sri Lanka, sad to say, are in such a situation. One

could, for instance, spot a hint of truth in the Cahiers du Cinéma’s

criticism of Clouzot: after all, it is said that the great man himself, though

naturally embittered, accepted their refusal to take his films seriously.

Laudable though such criticism may have been, could the same have been said of

our own self-labelled Cahiers’s criticism of Peries? I for once doubt

it. Who, after seeing Nidhanaya, can do otherwise?

This brings me to the third

subject of my letter. Mr Scorsese, I know for a fact that, partly owing to

reasons highlighted above, the cinema of my country has never gotten the sort

of international recognition it would have deserved. There are perhaps hundreds

of films here that, owing to momentary glitches sustained alongside brilliant sequences

(an essentially Sri Lankan flaw, I’m afraid), have never reached the dizzying

heights they aspired to. Within Sri Lanka’s 67 years of cinema, probably only

around 50 or 60 films have been made that deserve really serious attention. Lester

James Peries’ films, of course, are at the forefront of these.

Unfortunately, very few

filmmakers and critics abroad looked at Sinhala cinema with at least passing

interest – Roger Manvell, Donald Richie (who organised the 1970 MoMA

restrospect written of earlier), Pierre Rissient, and of course Lindsay

Anderson, who was a close friend of Peries were some of them. I feel that some

great masterpieces from our cinema have, hence, been missed by the world. They

are our contribution to world cinema, and that they have been missed, and not

just missed, but wilfully neglected, by our own people, leaves one little to

hope for. The sort of neglect accorded, say, to Ghatak’s films, of which A

River Called Titas was restored last year, thanks again to your wonderful

organisation.

Peries has made 20 films.

With the possible exception of two or three of them, all his other films, I

believe, would deeply interest you as a passionate lover of the cinema, as well

as a maker of films. Nidhanaya, for instance, was one of three films he

made for a major film production company (Ceylon Theatres). Taken together,

they represent Peries at his apex, the kind of work one could expect from a

filmmaker who, when provided with freedom and financing, could turn even the

most glossy stories into works of art that could belong only to the cinema.

|

| Golu Hadawatha |

Akkara Paha (Five Acres),

made in 1969, was the second, and may well be his least appreciated here. Once

again, the reason for this was politics, pure and simple. It eluded audiences chiefly

because Marxists saw it as an elitist apologetic for the resettlement programs

initiated by the government of the day. The plot of the film, briefly, traces

the downfall of a peasant and ambitious family, brought about by a weak but

essentially kind-hearted son. When their resources are stretched to the limit,

they are “saved”, in a sense, by this resettlement scheme, although at the cost

of travelling to the far outreaches of the country. Were it not for the MoMA

retrospective (where it was screened), I doubt it would have ever been

appreciated by critics here at all.

Of his other works, Gamperaliya,

as I said before, was the first Sinhala film to be restored by foreigners.

Considered his first real masterpiece (his first two films, though daring in

their approach to rural life, failed because they betrayed the director’s lack

of experience in their subject-matter), it won awards at New Delhi and Mexico,

and, in a government conducted poll in 1997, was listed as the second greatest

film made here, right after Nidhanaya. Based on perhaps the most

significant novel ever written in Sri Lanka, it traces, in a manner nearly akin

to the most poetic and rural of Renoir’s films, the downfall of the village

aristocracy with the onset of commerce. Unfortunately no 4k restoration of it

has yet been done.

Delovak Athara (Between Two

Worlds), which is my personal favourite, and which too was screened at the

Museum, was Peries’ third original story. Indeed, his biggest strength – and

this was largely owing to the talented scriptwriters he had at his disposal –

was his ability to concoct original stories. It proved what an auteur like

Peries could do with the resources of the cinema even with the thinnest of

plots. After all, isn’t that a hallmark which Godard was famous for (as an

additional point, a critic here at the time described it as the closest our

cinema had gotten to the Nouvelle Vague)? Its main incident – an

accident – is one around which the entire story, its set of characters and

every other incident revolves. Every “vantage point” in the film, so to speak, can

be approached only from the accident.

The incident, in other

words, serves as a sort of springboard for the development of the characters.

Its lack of popularity abroad, however, was owing to the milieu it was based

on. City-life (the film’s setting was in Colombo) was, back then, not much

preferred by an international audience that had come to expect village-rooted

stories from our country. For good or for bad, it did not find much of a

following abroad. But it contains perhaps the finest use of photography one can

hope to find in any of his films. Watching it, one is reminded of the most

poetic of Renoir’s films, for its sympathetic, witty and at times “conscious”

attitude towards its protagonist, who became, in my view, the very first

“Everyman” in the history of our cinema.

The protagonist’s qualms

over having caused the accident – and the fact that his parents implicate their

servant-boy to save him – would have done quite well for a social drama (or

melodrama), but Peries wisely steered from that territory. Locally it was a

mild success at the box-office, but some young critics here, erroneously, wrote

that it had plagiarised from Juan Bardem’s Death of a Cyclist, which, as

you may well remember, also includes an upper-class man facing his conscience

after killing a man on the road.

Rest assured that no such

plagiarism could have been possible: Peries was too original an artist to do

that. The only element common to both films, ironically, was the accident

itself, but while in Bardem’s melodrama-neo-realist masterpiece it is used as a

sort of indictment on bourgeois society, Peries never lets it go beyond being a

tool to examine his society from a humanist, sympathetic point of view.

Why I say it is Renoirean is

not because he has imitated his style, but watching its characters breathe,

talk and act, and its remarkable use of the camera, one is instantly reminded

of a film like, say, La Règle du Jeu. In fact there is a sequence in the

film, towards the end, when the camera up-closes on the protagonist’s face. The

effect of it, I can safely say, is quite similar to that of the close-up of

Marcel Dallio’s face by the calliope in La Règle du Jeu. In both

instances the camera is as delicate as a painterly canvas: it records, but does

not express too much.

Dallio’s face, as you will

remember, was that of a man overcome by pride for his latest musical

acquisition, but who is too modest to express himself (it is said that Renoir

had to shoot multiple takes to capture the look on his face perfectly).

Similarly in Delovak Athara, the camera in this sequence is used to

highlight the protagonist’s confusion: he is troubled enough as he is by the

accident, but now his qualms grow sharper with the servant-boy being implicated

in his crime.

At the same time, however,

he has grown too pampered and served upon to merely go up to the Police Station

and confess: hence the “two worlds” of the title. It may well have had the most

poetic use of the camera in all his films, Nidhanaya notwithstanding (with

Nidhanaya one is reminded of Albert Lewin’s The Picture of Dorian

Gray, that is to say, its noir-like feel, particularly strange because,

like Lewin’s adaptation of Wilde’s novel, Nidhanaya cannot be classed

under “film-noir” at all).

Lastly, Ran Salu (The

Saffron Robes). It is, admittedly, Peries’ most melodramatic film, and

there is a good reason for it – it was his only film whose script and

dialogues, not to mention plot, had all been written up by someone else: he had

no say in them at all. The writer of its story was P. K. D. Seneviratne, a poet

from the Colombo school, which had been famous for its Hardy-like evocative

praises of village life over city life. Their romantic conception of the

village was reflected in Ran Salu, which, though set in Colombo, still

championed rustic simplicity. It recounts the gradual transformation of a

city-bred girl into a virtuous woman influenced by Buddhism.

If the story sounds lacking

in authenticity, and seems too contrived in its championing of Buddhism, well,

it may be that it suits the structure of a simple morality play. There are two

antagonists – man and woman – who, Westernised, indulge in amorality before the

girl, made pregnant by the man, is ruined by his cruelty. In the end the girl

is won over to the nunnery by the protagonist, and the story ends on a hopeful,

if not spiritually reflective, note: in all, a blend of religion, sex and

morality.

Not that the film lacked any

appeal. Though it wasn’t a notable critical success at home, it won the Gandhi

Prize at New Delhi, and would later be brought for broadcasting by Irish

television. And though it has not been restored yet, the THIS Buddhist Film

Festival, in Thailand, did convert its 35mm reel into a watchable Beta version

some years ago.

These are just some of his

films, dear Sir, that I firmly believe will sustain your interest as a follower

of cinema. By no means am I making a plea for them to be restored immediately,

but, more pertinently, for you to be notified of their existence, for only by

watching them all can you at least hazard a guess as to their director’s style

and vision. Of course, their director has been forgotten by some, but today, fortunately,

he emerges as the true, much-loved giant that he had always been.

It seems unfortunate,

moreover, that his apex should have been reached at a time when the New Wave

had become fashionable, the results of which, for him, have been less than

satisfactory. By contrast, some of the Cahiers’s most treasured icons

included Renoir, Bresson and Howard Hawks. It was not blind adulation, mind

you, but adulation manifested with reason. No such valid reason existed for our

New Wave’s rejection of Peries, except perhaps their view of his craft being

“elitist”: in our country, it is fashionable to attach such labels to

filmmakers whose films demand even a modicum of sympathy and honesty from the

audience.

Indeed, the cameraman of Nidhanaya,

who himself was a maker of glossy, Madras-styled commercial films, once

described Peries as a “Hollywood artist” to me. Normally that wouldn’t mean

much, except that, even today, our directors prefer to follow Bollywood than

Hollywood. I do not call for them to blindly follow either, but nor would I

want them to ignore what is undoubtedly the place where art and commerce

intermixed so successfully as did nowhere else, and Tinsel-town, for all its

studio and star systems and its “go for the money” attitude, has on the whole

been far more agreeable to auteurs than Bollywood.

I feel that I have been

somewhat lavish in my praise of Lester James Peries. Well, this is not because

of a nostalgic reverie or age-old conservatism on my part towards him or the

past in general, but because in no other country has the Father of its cinema

been so isolated, so lonely, so underappreciated, as in here. One of his bon

mots has been that the Indian film, which for most of us here still remains

a source of perpetual pleasure, is “neither Indian nor film”, a witty saying

which not many will find appealing. Or, as Satyajit Ray once wrote, India “took

one of the greatest inventions of the West... and promptly cut it down to

size.”

As I have written before, we

in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) did the same with our cinema too. Why? Such a thing,

Mr Scorsese, seems to be a phenomenon peculiar to the South Asia – and yet we

know that South Asia has had as enriched and vital an artistic heritage as

Greco-Roman civilisation. Was it not South Asia that produced Kabir, Tagore,

Ravi and Uday Shankar, the Ajanta Caves, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Mughal

architecture, and of course Satyajit Ray? Why, I ask myself at times, was it

that the West’s most profound artistic invention since the sonata form in music

could be mutilated by so cultured a people?

To answer this, let me

rephrase my question – why did the cinema, in the silent era at least, develop

so profoundly in the United States, a country which, viewed dispassionately,

has had fewer centuries of civilisation and history than any in here? The

answer, for me, remains that owing to its lack of a proper literary tradition,

America was so vitally able to transform the most infantile of all the arts

into one of the most far-reaching inventions of the 20th century.

When sound did emerge, it was not ironic that a country most noted for its

artistic sophistication should have continued this transformation.

|

| courtesy: www.deviantart.com |

It was true that Keaton’s and Chaplin’s milieu was based in contemporary, urban settings unique to their countries: but with the admission of sound, the need to emphasize this regionalism, and the transmuting from the universal to the particular, became more pronounced. The fact that the artists who emerged in this age were human beings, pretty much like you and I – grossly flawed, but still redeemable – would have invested them with a wide appeal, but even that was constricted by the setting they were made to perform in.

What of South Asia? Unlike

in France, where music halls, theatre halls, concert halls and even vaudevilles

and cabarets afforded its people an array of entertainments, here in South

Asia, despite its civilisation, we did not have, and indeed could not afford,

such a thing. The closest thing to a theatre-hall culture India ever conjured

up, which held a wide appeal, was the Jatra play. Later, the South Indians and

the Parsees transplanted their dramatic forms in here.

What the former exported

here was christened “Nadagam”: I say “christened” because this crude form of

drama derived slight inspiration from Christian missionaries, who found in it

the perfect vehicle through which to preach the story of Christ, and the

Gospels, to illiterate villagers. By the 20th century, however, all

it had succeeded in becoming was a grotesque hybrid – a form of theatre that

attempted to be genuine in its depiction of rural life, but which was

constantly thwarted in that attempt by its own failings, not least of which was

a tendency to over-exaggerate even the most mundane incident in a play.

Like in India, no proper

cultured form of entertainment existed for us in Sri Lanka. The cinema, hence,

became even a form of ritual for the hundreds of thousands of illiterate

villagers, to whom it had become both affordable and mysterious. This was

further intensified by the fact that very many businessmen, intent on making

the most out of this innovative art form, formed so called “mobile picture

halls” that travelled from one village to another, almost like a circus. In

fact, one of our ablest filmmakers here, Sugathapala Senerath Yapa (who, like

Peries, was lambasted by the political film movement here during the 1970s)

became influenced by the cinema through these same picture halls.

To most villagers,

undoubtedly, the cinema would have been the most magical thing in their lives.

How, we can imagine them asking themselves, could real people be caught making

real speeches in locations (I won’t say real locations, because they were shot

in studios) and then, for the second time, be screened for us to see and hear

in all their glory and mannerisms on a big screen. It was unfortunate, at this

stage, that what the vast majority of villagers got to see were Bollywood

offerings – with the occasional Bengali product as well.

The tastes of these

villagers, understandably, became more pleiban, vulgar, you could say, and the

result of all this was that, when the first filmmaker of this country (B. A. W.

Jayamanne) set out to make films, he invariably went for the

Bollywood-influenced melodrama (it did not help, moreover, that his films were

all adaptations of his own plays, all of which were essentially “nadagam” in

style and speech). “Go for the money” was what would have worked in his mind

from film number 1.

Well, for the entire first

decade of our cinema, the trend and pattern of our films had already been

blessedly decided by this man. Together with his brother and sister-in-law (who

appeared as the chief actors in his films), he concocted story after story, all

revolving around the same theme – man meets woman, croons ballads of love in

almost every other scene, becomes cruelly estranged from her by external

forces, and finally reconciles when the bad guys are routed and thwarted.

This was, of course, until

Peries (who once told me that Citizen Kane moved him to filmmaking

proper – he was an arts critic at the time) came around to shoot a film

completely outdoors, with stage actors and non-professionals, and with a

limited, shoestring budget. It has been nearly 60 years since Rekawa was

made, and Peries’ erstwhile dream – the setting up of a National Archives – has

now been realised. Even if preservation may have given way to an era of

restoration, never mind, for without the impetus for preservation there would

have been no talk of restoration in the first damn place!

Sri Lanka has a serious

cinematic heritage behind her, but all too often – Peries himself has not

escaped this – serious artists have been subjected to malice, jealousy, spite

and the occasional, unjustified diatribe (there was a director here, whom I

interviewed, who once claimed that neo-realism – which he said had all but died

in the world today – was taken on by Ray and Peries at a time when it had

perished in continental Europe: an irony, given that he himself stated that his

first film had striking similarities to Bunuel’s Los Olvidados, which as

you will remember is nothing but neo-realism from frame number 1!).

I do not know, dear Sir,

what the situation in your country’s film industry is, but I suspect that, Day

of the Locust, Sunset Blvd and All About Eve notwithstanding,

it is not as prone to jealousy and ill-will – not to mention narrow-mindedness

– as ours is. Viewed in this regard, I suppose the fact that there not having

been any serious attempt at writing a book on his craft is unsurprising. The sad

truth is, no one seems bothered to do so, serious filmmaker and writer or not.

The exception, which seems refreshing to even hear of, was a book entitled Lester

James Peries: Life and Work, which unfortunately was a half-finished affair

owing to its author’s sudden death.

A more complete book – Lester

by Lester – is remarkably full of personal reminiscences and experiences,

which I know will prove fruitful for any lover of our cinema, but does little

to seriously examine his craft, in the same breadth as, say, Robinson’s The

Inner Eye. There is so much in this grand, humble maestro’s work that

simple shrieks for attention and study – which would even merit the attention

of a University dissertation – but for some reason has eluded most of us

Films have now become, as we

know, part of our cultural subconscious. No documentary, however well narrated or

filmed, can compare with the realism imbibed by City Lights, The

General and Modern Times. For what the documentary lacks – spirit, élan

– the so-called “fiction film” has in abundance. This is not to discount the

influence that documentaries have exerted on such visionary filmmakers as

Resnais, Ray or even Clouzot. Indeed, even Lester James Peries, before turning

to filmmaking, worked in our country’s Government Film Unit, where he came

under the influence of John Grierson and Ralph Keene.

This work as a

documentarian, with its painful fidelity to locales, manifests itself quite

abundantly in his later films. There has only been one filmmaker in the history

of the medium who conjoined lyricism, cinema and documentary all in one, and

Robert Flaherty, I have been told, is one director Peries has gone to again and

again. Renoir he counts as another subconscious influence; Ozu too, as well as Ray

– but in the final analysis, he is himself.

Grierson and Keene

notwithstanding, however, I doubt that Peries’ humanism, and his attitude to

human relationships and emotion, could have been influenced by his work as a

documentarian. There is too much of imagination and creativity in him to

suggest such a thing.

We in South Asia have a

proud cultural backdrop against us. Something went wrong, however, when

businessmen decided to turn the West’s most far-reaching art form into a tool

for earning money. The results of this are still apparent today: on the one

hand, you have stories which, no matter how appealing and innovative they may

seem, are replicas of the same formula, and on the other, filmmakers who have

managed, in their quest for overturning every form of cultural convention there

is in this country, to let technique supersede content in their films.

What most Lankans look for,

dear Sir – and their intelligence as cinemagoers has indeed risen since B. A.

W. Jayamanne’s days – are 1. a vigorous attitude to human relationships; 2. a

robust awareness of the country’s cultural fabric; and 3. respect, however

slight it may be, for that culture. I am not suggesting that filmmakers here

should tread the line of least resistance like timid ants – which is more than

what one can say of our commercial filmmakers – but that they should be more

aware that imitating Jean-Luc Godard or Alain Resnais or even Francois Truffaut

will bring them everything except the one thing without which no artist can

survive for long: public acceptance.

This acceptance over here

must, necessarily, come not from France, or Germany, or even the Maldives, but

from Sri Lanka. No amount of postmodern yarns or metaphysical abstractions can

hide dishonesty of treatment, and no amount of controversy parading as the

“truth” can subvert what our audience expects of any artist. Paraphrasing what

Ray once said, “de Sica, not Andy Warhol, must be our filmmakers’ inspiration.”

Life is art, art life: this

I have always believed. After all, isn’t that what your own films – Mean

Streets, Raging Bull, The Departed – engage in: the

presentation of life, however gritty it may be, rooted in a particular milieu,

yet transcending it at times to show us an aspect of human beings that is at

once regional and universal? Plain imitation, like plain refusal to dabble in

foreign art forms, can only lead to a film culture that withers away into the

dust. The biggest lesson, I think, that our self-labelled “serious” filmmakers

are yet to learn. Will they ever learn it? I sincerely hope so. Their biggest

teacher – how else can I conclude my letter to you? – can only be Lester James

Peries.

Thanking you,

Yours Faithfully,

No comments:

Post a Comment